The Real Lovely Ladies

One of the catchiest earworms of Les Misérables is “Lovely Ladies,” a song inspired by the French ladies of the night. It’s a dismal life for women, made even more tragic by the final refrain of the song after several jaunty, humorous verses. Today, we have a very different view of this career, but what many don’t realize is just how big and abysmal this business is.

Three Classes

In 1823 France, there were actually three different types of prostitutes: the courtesans, the lorettes, and the streetwalkers. Each of these women held various positions in their field and were treated very differently in terms of monetary value and the level of respect they were given.

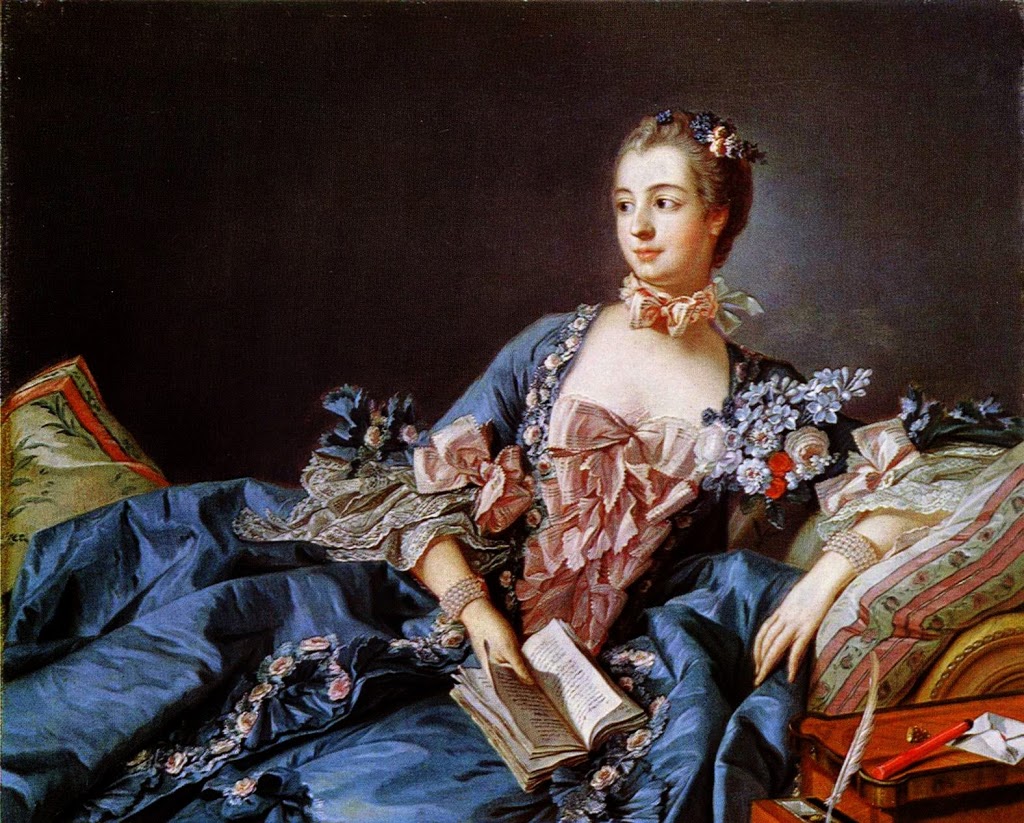

The highest level of prostitution was home to the courtesans. Described as “grand dames of commercial sex,” these women were usually mistresses of married men who chose their own lovers to climb the social ladder. Courtesans were generally well-respected women and many of them even had small jobs. They were treated like prized possessions, earning a good pay and dressing in the finest clothes. There was rarely any abuse of courtesans; they were like porcelain dolls to be loved and treasured. They were within the confines of the law and would never have to resort to streetwalking.

|

| The Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV |

The second tier belonged to the lorettes, another eloquent word that glamorizes the profession into something elegant and respectable. In many ways, lorettes were similar to courtesans, sharing many of the same perks. Lorettes were often decorated in expensive gowns and jewels, but because they themselves were bourgeois or aristocratic. In fact, no respectable man would introduce his lorette to his family. This wasn’t a honorable class, kept much more discreet than the courtesans (who were often acquainted with their lovers’ wives). Lorettes could be thought of as an accessory or a decoration, to be brought out on occasion for a bit of fun. Interestingly, lorettes were also legal in France.

|

| A lorette, lounging with her lover |

Streetwalkers scraped the bottom of the barrel. Women like our lovely ladies and Fantine fell into this category. Most of these women didn’t choose this lifestyle and ended up here as a last resort means of survival. Some, like Fantine, had families to support; some had been abandoned and only wanted a warm bed to stay in for the night. These women were lucky if they even had clothing to shelter them from the elements. They made about one sous per customer (compared to courtesans who might make 15-20 or lorettes who made 5-10). Instead of one man, they might see hundreds of men in their careers, men who would beat them and leave them for dead. Streetwalking was considered illegal if the women were unregistered at a specific brothel. Hanging out under the docks, though a decently organized operation, would not have been considered an official organization and therefore punishable.

|

| A group of rather well-dressed prostitutes propositioning men |

Ladies and the Law

All brothels were to be registered with the law in Paris and were expected to follow certain codes of conduct. Many times, the police would be called to both registered and unregistered brothels for complaints of noise and petty crimes. Ironically, most of the time, the men were far more at fault than any of the women. Many were abused, raped, and sometimes even murdered. Yet the police would come and take the ladies into custody for rule-breaking (contravention) and illness. Having venereal diseases was a crime as a prostitute for endangering the health of men who may spread it to their wives or other people. The sad fact is that the majority of these women developed diseases from the men, not the men from the women. Thousands of women were arrested under these charges. Most other crimes, like Fantine’s attack on Bamatabois, would be considered contravention, an umbrella term for “crimes against people.”

Once arrested, the Prefecture of Police would interrogate the prostitutes and decide, based on their circumstances, whether to free them or confine them to jail. The ladies would wait in holding for a period of one to two days to await release or imprisonment. If a prostitute was sent to prison, it was a facility specifically for prostitutes. In this facility, the women were actually decently provided for. They were given a good portion of food, including a piece and a half of bread, a small cup of soup, and four ounces of meat or starchy vegetables. They were rarely abused in prison and even had a courtyard they could visit three times a day. The women were put to work making clothes or other supplies for soldiers, cleaning, and cooking. Guards at these prisons weren’t overly hard on the women because prostitution generally wasn’t a very violent crime and they did their allotted share of work. For some of these women, the four to five months they spent safely in a “warm” bed with plenty to eat would be the best care they would ever receive.